UPDATE – NOVEMBER 9, 2023:

In her 39-page manifesto, former LCDR Sy’needa L. Penland clearly outlined Military Whistleblower retaliation she experienced while serving in the Navy.

The manifesto also described medical malpractice that has been ongoing since her release from the brig (prison) in late 2008.

In 2009, days following her discharge from the Navy, her medical-legal case was transferred to the VA to be “managed.”

The details surrounding the ongoing retaliation are in her memoir, “Broken Silence, a Military Whistleblower’s Fight for Justice.”

The evidence was also referenced and was enclosed with Penland’s statement to Senator Jon Ossoff, over a year ago.

Penland had hoped that Rep. Clyde and Senator Ossoff would take a bi-partisan approach in quickly resolving this matter, before it escalates into a “class action lawsuit.”

Such a suit would attract the attention of more disabled Veterans to join suit: “for wrongful injury while seeking medical treatment services from the VA’s medical consortium nationwide.”

Penland’s ongoing fight for justice is a true testament that Congress gives more lip service than actual measurable progress in helping the disabled veteran community.

Unfortunately, Congressional staffers are not paid “extra” to read lengthy complaints and evidence, which is clear in Clyde’s staffer’s response to Penland’s recent emails. No different than Ossoff’s response.

Penland is obviously aware of her Civil Rights protection, but is Representative Clyde?

A proper investigation into Penland’s case would will require an actual Congressional Committee review, which is costly and time consuming. MC.com warned Penland that complaints to legislators are never taken seriously. After the 30-day “courtesy review” is up, the case will simply go away.

A computer-generated response is sent to the Veteran, adding more insult than injury for having faith in a failed system. So, will Rep. Clyde seek better guidance from the Speaker of the House, Mike Johnson on how serious Congress needs to take Penland’s complaint?

As we see it, this is a clear failure to “prevent” ongoing retaliation against a military whistleblower. It also demonstrates ongoing failure to uphold Penland’s CRA protections.

Meanwhile, what about whistleblower protection for thousands of disabled Veterans mistreated in the line of duty, and while seeking healthcare recovery services from the VA. Only time will tell.

Penland’s case is all someone needs to help them decide whether to join the military or not. It’s the same story over and over again; military member discovers massive fraud and then, based on false charges, is railroaded right out of the service with a less than Honorable discharge.

Tell us again why you want to join the military? And, if you are currently on active duty, tell us again why you are considering staying in?

UPDATE – OCTOBER 20, 2023:

LCDR Syneeda Penland had written to her congressman asking him to intervene on her behalf. She received a response from his office today. All she wants is the military pension the Navy stole from her.

Penland received the following LETTER from Congressman Andrew S. Clyde.

While we hope she gets the Congressman to champion her cause, we normally only see just lip-service from politicians.

Politicians normally go along to get along and let the victims die by a thousand cuts of indifference.

Congress is supposed to be overseers of the military but frequently have been derelict in their oversight duties.

Given the fact that flag-ranking officers are routinely allowed to retire to avoid prosecution, Congress has continually and miserably failed to be good stewards of governance.

Maybe this time will be different. Let’s see what the Clyde-ster will do for his constituent.

BEGIN ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Military corruption never ends because there’s NEVER accountability for senior-ranking military officers, especially in the United States Navy.

The one thing that drives this website more than anything else is watching enlistees and junior officers carted off to prison while the admirals and generals are allowed to retire for committing the same crime or much worse.

The most common unequal application of military law is in the crime of adultery. A junior officer has a one-night-stand, while the admirals and generals are sleeping with everyone else’s wife. Flag-ranking officers quietly retire while others head off to prison.

Navy LCDR Penland was single and was accused of having a sexual relationship with married naval officer LTJG Mark Wiggan. He testifies at her court martial they DID NOT have an affair, but the Navy was hellbent on destroying Lieutenant Commander Sy’needa L. Penland.

In May 2008, LCDR Penland was convicted of…

- adultery,

- conduct unbecoming an officer,

- failure to obey a lawful order,

- and making a false official statement.

Her punishment was sixty (60) days in prison, $9,600 fine and a LOR (letter of reprimand).

The convening authority (RADM Len Hering) didn’t quite receive the Dishonorable Discharge for LCDR Penland that he had hoped for.

Normally military juries give the admirals whatever they want. Since she was in fact innocent, apparently the jury just couldn’t bring themselves to give LCDR Penland a Dishonorable Discharge.

To finish her off for good, a Board of Inquiry was convened to railroad LCDR Penland out of the naval service with an Other-Than-Honorable (OTH) Discharge depriving her of VA benefits and a military pension.

RADM Lenny Hering is alleged to have said to one of his staff, ‘I hope she (Penland) rots in jail.’ This utterance from RADM Hering got back to Penland. Never underestimate the Navy’s grapevine.

RADM Hering made sure LCDR Penland was thrown out of the military in the final months just prior to being eligible for a retirement pension.

Even if Penland committed adultery which she didn’t, ripping her retirement pension from her in the final days of active duty service is as low and vile as it gets. RADM Hering should be ashamed.

LCDR Sy’needa Penland proudly served her country for nineteen (19) years, nine (9) months and sixteen (16) days, but ended up with nothing to show for it but lots of pain and heartache.

Let that be a lesson to all potential military whistleblowers, attempting to protect taxpayer dollars will leave you nothing but pain, heartache and a struggle for the rest or your life.

There’s so much corruption and fraud in the military especially the Navy, that taxpayers are numb to it all and really don’t care about the plight of the military whistleblower.

These days, anyone on active duty who considers assuming the role of a whistleblower is an absolute fool. Congress doesn’t care, the military doesn’t care and the taxpayers don’t care. Why the hell do you care?

Remember what you were taught growing up, “assume” nothing. ASSUME means you’ll make an… “ASS out of U and ME”

Assuming the role of a whistleblower is a very stupid move. The entire system is rigged against you. The entire system is designed to find and destroy you. Let the admirals sneak off to Bermuda with their golf clubs and hookers; look the other way. Do not get involved. Say nothing.

Save your life and career and get your retirement pension like the admirals do. Just a word to the wise.

Let the admirals, generals and military contractors steal as much money as they can stuff in their pockets. Your life and livelihood is (or should be) much more important than doing the right thing. Just be careful the brass don’t set you up for the slaughter anyway.

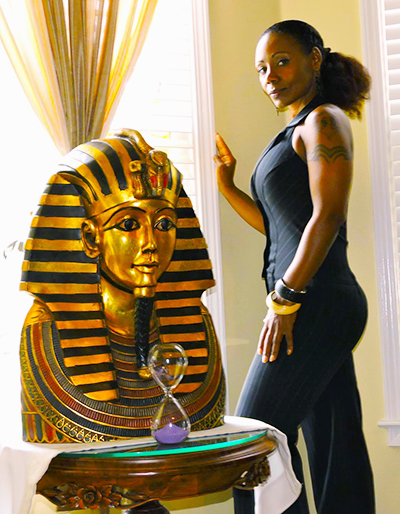

LCDR Sy’needa L. Penland

was the first woman

in U.S. military history

to be given a prison sentence

on the charge of adultery.

And for all we know, she was the first woman in military history sent to jail for a crime she did not commit. Without sex there can be…

- no adultery,

- no conduct unbecoming and

- no failure to obey a lawful general order.

LCDR Penland never had an affair with LTJG Wiggan as the Navy charged. The charge of adultery was therefore a false charge and her imprisonment for adultery was false imprisonment.

LTJG Wiggan was on the witness stand during the court martial being cross examined by Penland’s attorney Captain Callahan. The following is language from the transcript of trial on page 677…

Callahan: Did you get to know Lieutenant Commander Penland fairly well during that time?

Wiggan: Basically she was just the supply officer.

Callahan: Did you–did you have an affair with Lieutenant Commander Penland at any time?

Wiggan: NO.

Callahan: Have you ever had sexual intercourse with Lieutenant Commander Penland?

Wiggan: NO.

If you’d like to read it for yourself, here are pages 674-680 from the transcript of trial.

Apparently, the United States Navy has a problem with some very fundamental concepts. To establish the “crime” of adultery, the military must prove three elements.

The first and most important element of the “crime” of adultery is that the accused wrongfully had sexual intercourse with a certain person and at least one of the sex partners were married at the time. Penland was single, Wiggan was married.

Under oath, LCDR Wiggan categorically stated that he did not have sex LCDR Penland, but everyone in the court must have had just come off the flight line and still had their earplugs buried deep in their ears.

Either they didn’t hear what LTJG Wiggan said, or worse yet, they just ignored his answers as he testified at Penland’s court martial.

The Navy doesn’t need testimony from the other alleged lover in order to convict, they just ignore the testimony as if it never happened. Nothing could be more self-evident the military judicial system is rigged than the wrongful conviction and imprisonment of LCDR Sy’needa L. Penland.

AS A SIDE NOTE: On October 15, 2023, TheGatewayPundit.com published a story about soccer phenom Cristiano Ronaldo potentially being charged with “adultery” in Iran. An artist presented him with some of the paintings she did of him and he kissed her on the forehead and gave her a hug.

According to the Quran penal code, adultery is punishable by 100 lashes for unmarried people. It is punishable with death by stoning for married people, and in all cases of incest.

And just like the United States Navy, the Iranians are contemplating filing charges of adultery against the soccer superstar even though he never had sex. Ms. Hamami simply presented Ronaldo with a painting of him when he met with her and other fans before a game.

The Iranian penal code is a bit more harsh than the Navy’s UCMJ. In Iran, one can be stoned to death, the American Navy merely ruins your life and steals your pension from you.

The similarities between Iran and the United States Navy is the fact you can be destroyed without ever having any sex. The Iranians will take your life, the United States Navy will steal your pension and make you wear a scarlet letter ‘A’ for “adultery” with a Other Than Honorable Discharge.

Ronaldo was in Iran for Al-Nassr’s Asian Champions League game on Sept. 19, 2023. For his heinous crime of hugging he could be facing a minimum sentence of 100 lashes for giving the artist a hug in his appreciation for the painting. If he’s married, by Iranian law, he must be put to death.

If the Navy adopted the penal code from Iran, how many lashes would be handed down if everyone in the Navy were held accountable hugging. For that matter, how many lashes would be handed down to naval personnel for ACTUAL adultery?

To dispense “justice” based on the Iranian penal code, the Pentagon would need to hire hundreds of executioners wearing spiked leather wristbands to flog thousands of military personnel worldwide. Let’s not even talk about sentences that would be handed down for being gay.

Everyone who hugged someone or did the wild thing, except for flag-ranking officers would be a bloody mess. Don’t forget the military’s secret policy of allowing the admirals and generals to quietly retire to avoid any accountability. We’re pretty sure flag officers would choose retirement instead of being lashed 100 times. Besides the old admirals couldn’t take it, they’d end up cashing in their chips on about the 8th lash.

P.S. The last floggings in the United States were carried out in the state of Delaware in 1952 (the practice was abolished there in 1972).

President Biden may claim he was the one who eliminated flogging in Delaware. He was sworn in as Member of the New Castle County Council from the 4th district on January 5, 1971, and jumped from that job to U.S. Senator from Delaware on January 3, 1973.

WHY DID THE NAVY CONJURE UP A

BOGUS ADULTERY CHARGE AGAINST PENLAND?

Did the Navy just made up the adultery charge against LCDR Penland? Did the Navy threaten retaliation against LTJG Wiggan if he didn’t help in the court-martial lynching of LCDR Penland.

Navy prosecutors must have been surprised when LTJG Wiggan told the truth at trial saying he never had sex with Penland. Normally such an utterance would be cause to request a mistrial or have all charges dismissed. But no, not the Navy. They were going to get rid of her no matter what.

The United States Navy does not need evidence to convict anyone of anything. All they need is a corrupt convening authority and a corrupt prosecutor… and voila; the military achieves their desired conviction from a general court martial.

Was unlawful command influence (UCI) involved in the Penland conviction? You can bet on it. But, who needs UCI when you can charge someone with a violation even though the “perpetrator” didn’t commit the crime. Not some, but ALL elements of the crime must be present.

Unlawful Command Influence is where a senior officer usually in the chain of command either subtly implies or directly threatens the career of an officer serving as a court martial juror if he/she does not convict and “properly” punish the person the convening authority sent to trial.

We have no evidence UCI was used but like the United States Navy’s careless disregard of the evidence, we don’t need evidence to have a strong gut instinct that intimidated and coerced jurors had to bring in the “appropriate” judgement.

We believe Admiral Mike Mullen contacted RADM Lenny Hering and gave him marching orders to do whatever he could to ensure LCDR Penland received a harsh punishment which included a punitive discharge and the loss of her military pension.

If LTJG Wiggan admitted that he and LCDR Penland played hide-the-salami, why was only Penland the only one charged and convicted? Wiggan said under oath that he did not have sex with that woman Miss Lewinsky…. oops, wrong story… did not have sex with Penland.

So why didn’t the government drop the adultery charge and related charges against Penland? Again, in order to have violated the military’s statute of adultery in 2008, a penis had to be inserted into a vagina. No sex means no violation, but the Navy didn’t care, they convicted her anyway.

Wiggan had a duty to tell the truth and he told the truth to everyone on the witness stand. He said NO, he did not have sex with LCDR Penland.

After the kangaroo court adjourned, realizing the Navy was still attempting to railroad Penland into prison and out of the service, Wiggan could have offered to help set the record straight in other ways.

He could have contacted LCDR Penland offering to swear out a sworn statement saying that he and LCDR Penland never had an affair and that the court’s decision was morally reprehensible and a legal abomination. And, if the military attempted to suborn perjury, he could add those details as well.

A sworn statement could have potentially helped Penland in her quest to have the court martial reversed or nullified. But her struggle for justice and fairness continues against an uncaring and indifferent military judicial system.

LTJG could have contacted MilitaryCorruption.com since we have been exposing corruption in the military online since July 2000. We could have written this article fifteen years ago.

RADM Lenny Hering retired and is enjoying his military pension. The prosecutor is probably retired as well. All the others who knew LCDR Penland was being railroaded out of the service on bogus charges are probably living the good life as well. That’s the current system for ya!

WHAT’S THE REAL REASON?

We ask ourselves, what’s the real reason for the over zealous prosecution and persecution of LCDR Penland? Why the disparity of justice? Again, if the Navy believed that adultery had actually occurred, why weren’t both Penland and Wiggan charged with adultery?

Why are low-ranking military personnel handed such severe punishments for a so-called “crime” that bears no malice? Or in Penland’s case, for a “crime” that never occurred?

Was it because Penland was female? Doubtful. In a sexual relationship, the female gets a pass while the male counterpart takes in on the chin. We know this all too well from our school days.

When a male teacher has sex with a female student, he is all but sent to the gas chamber. When a female teacher has sex with some 16-year-old boy, the punishment (if any) isn’t nearly as severe and the student is called “lucky” by teachers and students alike.

Was it because Penland is an African-American? We are not race-baiting. We loath the race-baiters. But the question must be asked; was the disparity in punishment because she was African-American?

For the record, Penland is genetically more Native American than African American. Unlike Senator Elizabeth Warren, LCDR Penland actually does have Native-American blood.

Was it because LCDR Penland was a mustang officer? For those who don’t know, a mustang officer is a naval officer who received his/her commission from the enlisted ranks of the Navy. Mustang officers are frequently confronted with prejudice from other naval officers.

Or, was it about the money? The Navy has used the court martial process before to silence and remove anyone blowing the whistle on fraud that could embarrass the flag-ranking fraternity in Washington.

LCDR Penland noticed inappropriate expenditures, especially with regards to how government credit cards were being misused. That didn’t sit well with the brass hats at all. Did Penland stumble on things that could have led to exposure of much bigger frauds by the admirals? You can almost bet on it.

Was the attack on Penland about the money or about the affair that never took place? Normally, it’s always about the misappropriation of taxpayer dollars that ruffles feathers the most. The chain of command had to get something on her so they began to dream up violations of the UCMJ.

Her so-called affair with LTJG Wiggan turned out to be just a figment of the JAG prosecutor’s imagination. Her professional demise wasn’t about an alleged affair, it was more than likely about the wholesale theft of millions of taxpayer dollars.

You see, the United States Navy does not like pesky bean-counter supply officers attempting to balance the books. And, they really don’t like supply corps officers with a high sense of personal integrity that cannot be bullied or coerced. All they want is for the books to look like they are balanced.

Recall what happened to Navy Chief Petty Officer Michael Tufariello when he reported massive and chronic payroll fraud in the naval reserves in Dallas, Texas. Once again the United States Navy showed their true colors.

They threw Chief Tufariello in a military mental hospital falsely claiming he was a suicide risk.

This effectively discredited his attempt to blow the whistle on enormous payroll fraud involving 800 drilling reservists.

Just like LCDR Penland’s case, the Navy also threatened Tufariello with taking away his pension just prior to his retirement.

Since her removal from the Navy, Sy’needa Penland has found life hard.

While her military pension and all other benefits were stolen from her, she continues to fight on.

Recently she contacted her elected representatives Congressman Clyde and Senator Jon Ossoff asking for their involvement to get the retirement pension she was cheated out of.

Here are court documents pertaining to Penland’s ongoing struggle for some sliver of fairness from a rigged military system…

August 7, 2009, PENLAND v. NAVY SECRETARY RAYMOND MABUS

(Denial of Injunction by U.S. District Court of Columbia)

April 20, 2016, PENLAND v. NAVY SECRETARY RAYMOND MABUS

(Summary Judgement)

Here are Penland’s most recent communiques in her never-ending quest to be treated fairly by the country that she served for a large chunk of her life…

- October 6, 2023, Letter to Congressman Andrew Scott Clyde (R-GA)

- February 28, 2022, Letter to Senator Thomas Jonathan Ossoff (D-GA)

- April 29, 2022, Update letter to Senator Thomas Jonathan Ossoff (D-GA)

The military decided to quietly change the wording in the UCMJ removing the word “adultery” from the UCMJ statute. Sex between two people where one or both are married is now called “Extramarital Sexual Conduct.”

LCDR Penland’s recent letter to Congressman Clyde brings her case up-to-date.

While adultery in the military is the focus of our article, the primary take away from all this is how the military can arbitrarily pick and choose whose lives they want to ruin.

It’s a classic case of how someone can be convicted in the military for something they never did.

“What’s good for the goose is good for the gander.” This means that one person or situation should be treated the same way that another person or situation is treated.

Penland was sent to jail while the married lieutenant junior-grade got a pass all for a sexual relationship that never occurred. No sex, no adultery!

Equal Justice Under Law simply does not exist in the United States military. Ft. Leavenworth is only for enlisted and junior officers.

The American military judicial system has adopted an old soviet tactic…

Lavrentiy Beria, was the most ruthless secret police chief in Joseph Stalin’s reign of terror. He bragged that he could prove criminal conduct on anyone, even the innocent. “Show me the man and I’ll show you the crime” was Beria’s infamous boast.

In the United States Navy, it’s… “show us the woman and we’ll conjure up an adulterous affair.”

And, that’s just the way the admirals and generals like it, thank you very much. It is terribly wrong to destroy anyone over an act that does not bear malice. It’s even worse to convict someone who is innocent.

Depriving LCDR Sy’needa Penland of a retirement pension just a few months before she was eligible for retirement is as vile and petty as any person or organization can get. In naval jargon, it’s called being lower than whale turds.

The United States Navy should be ashamed for their despicable decision to use and manipulate their judicial system to rid themselves of a whistleblower through a court martial process.

Falsely charging and convicting LCDR Penland demonstrates just how much the Navy wanted to rid themselves of a persistent whistleblower who was not going to falsify the balance sheets to protect the admiralty.

The adultery that never occurred mislead many others outside of the Navy.

In June of 2016, Deborah L. Rhode wrote the book, “Adultery: Infidelity and the Law” giving readers a legal view of the LCDR Penland adultery case.

Author Deborah Rhode compared LCDR Penland’s so-called adultery to the affair that General David H. Petraeus had with Paula Broadwell.

In 2011, a law review was written by Katherine Annuschat which addressed the legal issues surrounding adultery in the military and cited LCDR Penland’s case several times.

We encourage our readers to first read LCDR Penland’s letter to her congressman, then read the following law review.

When reading, think of all the admirals and generals who continue to commit acts of adultery that will never held accountable. Compare that to all the people in military prisons, a percentage of which are actually innocent.

To have integrity, there must be an equal application of the law and the accused must first must have actually broken the law.

Brew a pot and settle in for a well-researched study about adultery in the military…

AN AFFAIR TO REMEMBER:

THE STATE OF THE CRIME OF ADULTERY

IN THE MILITARY

by: Katherine Annuschat, published June 2011

TABLE OF CONTENTS

I. INTRODUCTION

II. THE HISTORY OF CIVILIAN ADULTERY STATUTES AND THE CIVILIAN APPROACH TO ADULTERY

III. THE ORIGINS OF THE MILITARY CODE AND ITS APPROACH TO ADULTERY

IV. HOW THE PROSECUTION PROVES ADULTERY UNDER ARTICLES 133 AND 134

A. The Offense of Adultery Under Article 134

1. Prejudicial to Good Order and Discipline

2. Discrediting to the Military

B. Prosecuting Adultery Under Article 133

V. THE JUSTIFICATIONS FOR CONTINUING TO PUNISH ADULTERY IN THE MILITARY

A. Preserving Honor in the Armed Services

B. Upholding Good Order and Discipline

C. Maintaining the Trust of the American People

VI. WHY THE MILITARY WOULD BE BETTER OFF WITHOUT THE CRIME OF ADULTERY

VII. CONCLUSION

I. INTRODUCTION

In May 2008, a general court-martial convicted nineteen-year Navy supply officer Lieutenant Commander Syneeda Penland of adultery and sentenced her to sixty days in the brig.

As a result of her conviction, the Navy dismissed Penland just a few months short of retirement, causing her to lose her severance pay, health benefits, and military pension.

Penland—unsuccessfully—fought her dismissal, alleging that the adultery accusations were made in retaliation for her attempts to expose financial improprieties in her command.

The adultery charges stemmed from an alleged sexual relationship between Penland, who is single, and a married junior officer, Lieutenant (junior grade) Mark Wiggan.

Wiggan, on the other hand, was not prosecuted.

In 2003, Army Captain James Yee faced a slew of serious criminal charges, including espionage, spying, and aiding the enemy.

When these charges fell through, allegedly because the evidence against Yee amounted to nothing, the Army brought significantly less serious charges against him, including mishandling classified documents, possessing pornography, and adultery.

At Yee’s first hearing on these new allegations, the prosecution did not begin by presenting evidence of the more serious charges but with introducing a witness to the adultery accusation. Yee’s parents, his wife, and four-year-old daughter were present and listened as a Navy lieutenant testified about an affair with Yee. After this hearing, the prosecution asked for a delay and eventually dropped all of the charges.

Gary Solis, a former prosecutor for the Marines and current adjunct professor of law at Georgetown University, stated that the Army pursued the adultery charges to “embarrass and humiliate” Yee when the case had “turned to crap.”

Under military law, adultery is a crime under Article 134 of the Uniform Code of Military Justice (UCMJ). According to the Manual for Courts-Martial (MCM), a servicemember is guilty of adultery under article 134 when the servicemember has sexual intercourse with an individual, and at that time, either of the two is married to someone else.

Now, U.S. Administrative Law Judge at Social Security Administration, yet another member of the cabal who, according to Penland, helped to railroad her into prison.

Hence, a servicemember does not need to be married to be found guilty of adultery. In addition, the adulterous conduct must be prejudicial of good order and discipline in the armed forces, or be “of a nature to bring discredit upon the armed forces.” An officer may be punished for adultery under article 133 as well, as long as the court finds the adulterous conduct meets the standard of conduct unbecoming an officer and a gentleman.

Even though criminal sanctions for adultery in the civilian world have played a role in American jurisprudence, that role has been relatively minor.

In fact, the majority of states have now decriminalized adultery. Moreover, even in the states with adultery statutes still on the books, adultery prosecutions are nearly unheard of. And after the Supreme Court’s decision in Lawrence v. Texas, adultery prosecutions may even violate a citizen’s constitutional right to privacy.

In contrast, the military still regularly pursues adultery prosecutions, evidenced by the 900 men and women court-martialed in the 1990s alone for charges that included adultery. Concededly, many of these cases also involved other, more serious charges, such as rape.

Even so, several high-profile cases in recent years have led observers to criticize the military for what many see as a conscious decision to pursue adultery charges against servicemembers in an effort to publicly humiliate them.

Recognizing the rarity of adultery prosecutions in the civilian world, it may be surprising that adultery is still actively prosecuted under military law.

Yet, the American people may be even more surprised to learn that civilians who accompany the United States military to combat zones around the world are now also subject to the UCMJ, and, as a result, possible prosecutions for adultery.

The recent cases against Penland and Yee demonstrate with clarity the military’s willingness to pursue adultery prosecutions for questionable motives. In light of this fact, and the obsolescence of these statutes in the public mind, adultery should be removed from the enumerated offenses under article 134.

II. THE HISTORY OF CIVILIAN ADULTERY STATUTES AND

THE CIVILIAN APPROACH TO ADULTERY

Adultery has been a crime in most American jurisdictions since the colonial period, with sanctions ranging from death to a fine. Historically, two main rationales justified the punishment of adultery as a crime. One theory for punishing adultery was to preempt violent acts of vengeance by providing an alternative way to right the wrong against the husband.

Under this view, adultery was considered a private wrong that invaded a husband’s rights over his wife and not as a wrong against society.

This rationale for punishment, though influential in early English law, did not carry the same weight with the Puritans in America. Instead, the rationale for prosecuting adultery in early American history was mainly ecclesiastical.

The Puritans punished adultery because, as an offense against God, it amounted to a threat against society itself. These early Americans made adultery with a married woman a capital offense, but convictions were rare due to views that the sentence for the crime was too harsh.

The Puritan belief lived on in American jurisprudence and most states made adultery an offense by statute. Many of these statutes, however, were poorly enforced and ignored by many Americans, but still provided opportunities for blackmail and extortion.

In 1955, drafters of the Model Penal Code recommended that adultery be decriminalized, taking the position that it was merely private immorality, falling outside the scope of criminal law. In response, many states removed adultery statutes from their books.

In the states that still have an adultery statute intact, the crime is usually not more than a misdemeanor, with punishment often only amounting to a small fine.

Even though the crime of adultery still exists in more than twenty jurisdictions, one will be hard-pressed to find a state that will pursue adultery prosecutions. This scarcity of prosecutions reflects an unwillingness by the government to bring a criminal action for adultery.

Moreover, there exists a strong argument that adultery is protected under the constitutional right of privacy. The Supreme Court in Lawrence v. Texas stated that “liberty gives substantial protection to adult persons in deciding how to conduct their private lives in matters pertaining to sex.”

Although this decision only applied specifically to sodomy statutes, the language the majority used suggested that any private, adult, consensual, sexual conduct should receive some protection under the constitutional right of privacy.

Under this definition, adultery is a type of conduct that would fall under the privacy right. Tellingly, Justice Scalia’s dissenting opinion specifically mentioned adultery laws as being called into question by the decision. Nevertheless, the Supreme Court has not yet expanded the right to privacy to include adultery, and many state adultery statutes remain.

Even though adultery prosecutions have declined significantly in the civilian world, this country has not grown immune to the shock and scandal involved in affairs of the heart. Several high-profile adultery scandals have rocked the American public in recent years.

These include former New York Governor Eliot Spitzer’s escapade in a prostitution ring and South Carolina Governor Mark Sanford’s secret affair with an Argentine woman. Even though both of these men were powerful figures in their respective states—both of which still have adultery statutes on the books—neither faced even a threat of prosecution under his respective state adultery statutes.

The reactions to both of these cases suggest that, although Americans still disapprove of adultery, most do not expect an extramarital tryst to merit criminal prosecution, even when committed by some of the most important figures in government.

III. THE ORIGINS OF THE MILITARY CODE AND ITS

APPROACH TO ADULTERY

The purposes of military law, as listed in the MCM, are promoting justice, “maintaining good order and discipline in the armed forces,” promoting efficiency and effectiveness in the military, and strengthening the national security of the United States.

Commander, Navy Expeditionary Combatant Command, another member of the cabal who contributed to LCDR Penland’s downfall.

Military law has jurisdiction over all branches of the armed forces, including the Navy, the Army, the Air Force, the Marine Corps, and the Coast Guard. In addition, civilians who accompany the armed forces during “contingency operations” now fall under the jurisdiction of military law. This includes any contractors and civilian employees who are currently in Iraq or Afghanistan.

Congress first implemented the UCMJ in May of 1950. Congress drafted this legislation during the aftermath of World War II, at a time when lawmakers first and foremost sought to protect the rights of military personnel.

The UCMJ protected servicemembers against self-incrimination fifteen years before Miranda v. Arizona, “permitted relatively broad access to free counsel, and incorporated many of the best features of federal and state criminal justice systems.” This legislation was landmark in that it created the fairest system of court-martial of any country in the world at that time.

When Congress enacted the UCMJ, it incorporated two types of offenses: civilian crimes, such as murder, and special military offenses, such as dereliction of duty. Congress based the definitions of the civilian crimes included in the UCMJ on the laws of Maryland at that time.

It included these crimes in order to standardize military law with civilian law, demonstrating a belief that servicemembers should not be exempt from the same crimes for which their civilian counterparts are accountable.

Congress enacted the UCMJ as a series of federal statutes to create the substantive criminal provisions for the military. In contrast, the MCM is a compilation of military common law and court-martial procedural and evidentiary rules.

The MCM also creates many substantive crimes not explicitly present in the UCMJ, with the purpose of clarifying the general criminal statutes of the UCMJ. One example is adultery, which is included in the MCM as one of more than fifty examples of types of conduct that merit a prosecution under article 134.

The MCM also differs from the UCMJ in that it is not enacted by Congress but by the executive branch and members of the Department of Defense and military branches. In that sense, crimes created by the MCM, such as adultery, come directly from the rule-makers in the military, rather than Congress. Perhaps this is one reason why the military has become disjointed from the civilian world in this field.

Adultery has long affected military life. Anecdotal accounts by servicemembers portray adultery in the military as just as common as in the civilian world, if not more so.

Their comments range from characterizing adultery as being “as commonplace as fleas on a buffalo,” to claims of knowing several high-ranking officers “who are well known to be involved in such activity [as adultery] and it is simply winked at.”

Despite the long history of adultery in the military, there are very few cases pre-1984 that involve a prosecution for simple adultery under the general article, article 134.

A probable explanation for this lack of prosecutions is that the original UCMJ did not include a statute prohibiting adultery.

In 1984, however, an amendment to the MCM brought the addition of an adultery offense to the black-letter military criminal law for the first time.

Rather than a uniquely military offense, adultery represented a crime originating in the civilian code, and in that area the UCMJ has usually striven to mirror trends in the civilian world.

Given that fact, it is perplexing that as adultery prosecutions have fallen out of favor in the civilian world, they have gained considerable momentum in the military.

Besides the much greater number of adultery prosecutions in the military than in the civilian justice system, the penalty for adultery is also much harsher for servicemembers. In Maryland, for example, the state punishes adultery as a misdemeanor with a $10 fine.

In stark contrast, the MCM lists the maximum penalty for adultery as “Dishonorable Discharge, forfeiture of all pay and allowances, and confinement for one year,” essentially equating the offense to a felony.

In this area, it appears that the military is holding its personnel to a much higher standard than the rest of the country.

Moreover, even if the highest punishment is not meted out when the servicemember is formally charged with adultery, the offense still appears in the servicemember’s permanent military record with a negative annotation. This type of mark on a servicemember’s record could effectively end a military career by making promotion impossible.

When charged with an offense, a servicemember’s commanding officer often has discretion as to whether to punish the offense by court-martial or by nonjudicial punishment. Nonjudicial punishment is a disciplinary measure that is less serious than a trial by court-martial but more serious than administrative corrective measures.

Normally, a nonjudicial punishment may only be pursued for a minor offense, and an offense is generally minor when the maximum punishment would not include a dishonorable discharge or confinement for longer than one year.

Accordingly, adultery would not usually qualify as a minor offense because it may result in a dishonorable discharge, and therefore it should be tried by court-martial without the option for the lesser nonjudicial punishment.

The other method to punish an offense in the military is by court-martial. Courts-martial may try any offense under the UCMJ and the laws of war to the extent permitted by the Constitution and may try any person subject to the UCMJ. This includes active duty military personnel, certain retired personnel, certain reservist personnel, and civilians who accompany the military on contingency operations.

There are three types of courts-martial: summary, special, and general. Out of the three types of courts-martial, the general court-martial is the most serious forum and also the most similar to a civilian court.

Any offense and any punishment under the UCMJ has the potential to be tried and adjudged in a general court-martial, though this forum is usually reserved for the most serious crimes.

Due to the severity of its maximum punishment, adultery is considered more serious than a minor offense and thus must be tried by a special or general court-martial. In order to convict a servicemember of adultery at a court-martial, however, the MCM requires that the government prove more than just an indiscretion.

IV. HOW THE PROSECUTION PROVES ADULTERY UNDER

ARTICLES 133 AND 134

The MCM lists the crime of adultery under article 134. To establish this crime, the military must prove three elements:

- That the accused wrongfully had sexual intercourse with a certain person;

- That, at the time, the accused or the other person was married to someone else; and

- That, under the circumstances, the conduct of the accused was to the prejudice of good order and discipline in the armed forces or was of a nature to bring discredit upon the armed forces.

For officers, the government may also charge adultery under article 133, the only difference being that in place of the third element, the prosecution must prove that the conduct “constituted conduct unbecoming an officer and a gentleman.”

A. The Offense of Adultery Under Article 134

To be found guilty of adultery under article 134, the prosecution must not only prove that adultery took place but also that the conduct was prejudicial to good order and discipline or was of a nature to bring discredit upon the armed forces.

The MCM explains prejudice as conduct that has “an obvious, and measurably divisive effect on unit or organization discipline, morale, or cohesion, or is clearly detrimental to the authority or . . . respect toward a servicemember.”

It further stipulates that, in order to qualify as behavior that discredits the service, the conduct must be sufficiently open or notorious in nature “to bring the service into disrepute . . . or lower it in public esteem.”

The MCM makes clear that private adulterous conduct may be found by a court to be prejudicial to good order and discipline, but it does not explain how.

To assist a military judge or commanding officer in determining whether the adulterous conduct is prejudicial to good order and discipline or is of a nature to bring discredit upon the armed forces, the MCM provides a list of eight factors to consider:

- (1) the accused’s and the coactor’s marital status and rank or relationship to the Armed Forces;

- (2) the military status or relationship to the military of the accused or coactor’s spouse;

- (3) the impact of the relationship on either’s performance in the military;

- (4) the misuse of government time or resources to facilitate the relationship;

- (5) whether the conduct persisted despite orders to desist, “the flagrancy of the conduct,” and whether the adultery was accompanied by other UCMJ violations;

- (6) the negative impact of the conduct on the units of the accused, the coactor, or the spouses of either;

- (7) whether the accused or coactor were legally separated;

- (8) whether the adultery was an ongoing relationship or more remote in time. These factors, added to the MCM in 2002, are just that—factors. Even though the addition of these factors demonstrates a desire by the military to limit the circumstances of adultery that merit a judicial intervention, they have not yet been effective at stopping the arbitrary prosecution of adultery in the military.

They are not additional elements that the prosecution must prove but only issues that the court may consider when determining whether the conduct was sufficiently detrimental to good order and discipline or to the reputation of the armed services.

The court-martial is still free to convict for adulterous conduct that meets only a few of these factors or even none of them, as long as the court decides that the conduct was in some way prejudicial or discrediting to the service.

1. Prejudicial to Good Order and Discipline

The language of the MCM makes clear that, in order for adulterous conduct to merit a prosecution under the prejudice prong, it must be directly prejudicial to good order and discipline. This means the conduct must have some measurable effect “on unit or organization discipline, morale, or cohesion, or is clearly detrimental to the authority or stature of or respect toward a servicemember.”

The court-martial in United States v. Johnson reflected these same sentiments, stating that article 134 prosecutions are “confined to cases in which the prejudice is reasonably direct and palpable.”

This same court, however, held that “offenses involving moral turpitude are inherently prejudicial or discrediting” to the service but failed to supply an exact definition of what constitutes moral turpitude.

Many courts-martial using this same language have found that conduct involving moral turpitude is inherently prejudicial, consequently allowing the prosecution to fulfill its burden of proving this essential prong just by alleging that the conduct of the accused was immoral.

A definition of moral turpitude based on court-martial case law, however, is hard to come by.

The absence of a clear definition of immoral conduct could be explained in many ways.

First, there are presumably hundreds of punishable acts that a judge could find to be morally reprehensible, and it would be nearly impossible to list them all.

Second, when courts have attempted to define conduct involving moral turpitude, they often resort to listing examples of immoral conduct rather than endeavoring to describe what actually makes conduct morally wrong.

Because of this, no discernable pattern emerges in case law from which one could predict what the court will deem as immoral and what will require additional proof that the conduct is prejudicial.

For example, the court in United States v. Light stated that accepting a bribe and cheating were examples of immoral conduct, whereas borrowing money from a subordinate was an acceptable act.

By contrast, in United States v. Hunt, the court found that negligent homicide did not involve moral turpitude because it was a misdemeanor under the local civilian law. Furthermore, even when the courts-martial have addressed the same conduct, they still have not agreed on whether it is immoral.

This is exemplified by the courts’ treatment of false swearing. The court in United States v. Greene stated that false swearing is an offense that involves a degree of moral turpitude, whereas the court in United States v. Johnson stated that lying may be dishonest but is not “per se wrongful or discreditable.”

All of these cases illustrate the problem with basing punishment on morality: morality is intrinsically subjective. This is especially problematic for adultery, a type of conduct defined from the beginning of American jurisprudence by its immoral character.

Even though recent decisions have defined adultery as not involving moral turpitude and thus not inherently prejudicial, the U.S. Navy Court of Military Review in United States v. Ambalada declared that adultery was an offense against the morals of society.

This inconsistency is troubling, given that a finding that adultery is immoral automatically makes the act prejudicial to good order and discipline, thus significantly relieving the government’s burden of proof in establishing the crime of adultery under article 134 and essentially eliminating the necessity of the factors.

This might also provide an explanation as to why, in some cases, the court has not required much in the way of proof of the prejudicial effect of the adultery, suggesting that it has instead relied on its own private finding that adultery is immoral and thus inherently prejudicial.

2. Discrediting to the Military

The MCM allows the prosecution an alternative way to prove the damaging effect of an adulterous act—by proving that the act had a tendency to discredit the armed services.

The MCM describes discredit as meaning “to injure the reputation of the armed forces and includes adulterous conduct that has a tendency, because of its open or notorious nature, to bring the service into disrepute, make it subject to public ridicule, or lower it in public esteem.”

The very language of the MCM states that the prosecution does not need to prove any actual damage to the service’s reputation but only that the conduct had the tendency to produce that damage.

By not requiring the prosecution to prove any definitive damage to the military’s reputation, this element becomes relatively easy to satisfy. The court in United States v. Velazquez found that because others were aware of the adultery, it was sufficiently service discrediting.

The court did not require any proof that this knowledge led to a condemnation of the service or the servicemember, only that outside knowledge of the conduct existed.

This type of logic assumes that anyone who knows about adulterous conduct automatically disapproves of both the act and the entire organization associated with the adulterer, and consequently this knowledge brings the entire military into disrepute.

Based on the evident disapproval of criminal prosecutions for adultery in the civilian world, it does not seem to fit that prosecuting adulterers is the way to win the approval of the American public.

In any case, the Velasquez decision demonstrates that any proof of knowledge of the affair is sufficient to find the conduct as tending to discredit the armed services.

Disagreement has arisen among the courts, however, on whether proof of awareness of the conduct is necessary to prove a tendency to damage the service’s reputation.

One line of decisions states that civilians must be aware of the behavior and military status of the offender in order to establish that the conduct is service discrediting. United States v. Perez represents this view.

In Perez, the court held that the government did not meet its burden of proving that the defendant’s adultery was prejudicial to good order and discipline. Furthermore, the court found that because the government did not show that civilians knew about the affair, the conduct was not of a nature to bring discredit on the armed forces.

This paradigm seems logical. In order for the actions of one servicemember to tend to cause the public to look down on the entire military, there reasonably must be some public awareness of this conduct.

Another line of cases exists, however, that does not require any notoriety to find that the conduct had a tendency to bring the service into disrepute.

In United States v. Mead, for example, the court emphasized the language of the MCM by pointing out that the court was only concerned with conduct that was “of a nature to bring discredit upon the armed forces because of its tendency to bring the service into disrepute or lower it in public esteem.”

Based on this language, the court found there was no requirement that the public be aware of the conduct or the accused’s military status in order to establish the conduct as tending to bring the service into disrepute.

Similarly, in United States v. Nygren, the Coast Guard Court of Criminal Appeals, when presented with the argument that the public must be aware of the appellant’s underage drinking in order for it to tend to bring the service into disrepute, stated that it knew of “no binding authority to that effect” and believed “the contrary [was] true.”

Admittedly, the cases in Mead and Nygren dealt with prosecutions under the general offense of article 134, for possessing child pornography and for underage consumption of alcoholic beverages, respectively, and not a specific enumerated offense under article 134, like adultery.

Thus, the cases that specifically require public awareness of adultery to find the conduct discrediting to the service may be controlling on this issue. Regardless, this disagreement among the courts creates uncertainty about what facts the prosecution must establish to prove this element, allowing the court to give the prosecution leeway when it deems the conduct immoral.

Even with the two separate approaches to proving that the adultery is damaging enough to justify a criminal prosecution under article 134, in reality, the courts-martial often view these approaches as one and the same and discuss the two elements interchangeably.

By not requiring any specific showing of fact for these two disparate elements, the courts-martial give the prosecution great latitude to prove them both. This tends to suggest that the court will apply its own imprecise standard on a case-by-case basis, thereby providing no predictability as to which adulterous conduct will actually violate article 134.

B. Prosecuting Adultery Under Article 133

An officer may also be convicted of adultery under article 133. This article, unlike article 134, applies only to commissioned officers, cadets, and midshipmen in the armed services.

To present a successful case under article 133, the prosecution only needs to prove that the individual officer committed the predicate acts and that those acts, under the circumstances, “constituted conduct unbecoming an officer and gentleman.”

When an officer is charged with a crime already included under other articles, such as adultery, the burden of proof for conviction under article 133 is distinct, requiring, in addition to elements of proof under the other offense, that the conduct constitutes unbecoming conduct.

Consequently, no matter the charge, the appropriate standard for conviction is whether the conduct is dishonorable enough to constitute conduct unbecoming an officer and a gentleman.

The explanation in the MCM provides that every officer must have certain moral attributes, but it does not spell out what these attributes are.

It further explains that an officer who lacks the expected level of morality exhibits this by “acts of dishonesty, unfair dealing, indecency, indecorum, lawlessness, injustice, or cruelty.”

It goes on to provide a list of examples that would constitute conduct unbecoming an officer, including cheating on an exam, public association with known prostitutes, failing to support the servicemember’s family without good cause, and committing any crime involving moral turpitude.

The type of conduct that amounts to unbecoming conduct is further described by the MCM as any acts in an official capacity that compromise the officer’s character and any acts in an unofficial capacity that compromise his standing as an officer.

Stated more succinctly, conduct unbecoming includes any behavior at work that reflects badly on one’s personal character or any behavior at home that indicates an officer is professionally incompetent. Thus, article 133 regulates both public and private conduct.

Article 133 focuses on how the conduct reflects upon the officer not only as an individual but also as a representative of the armed services. First, an officer, unlike most enlisted servicemembers, is in a position of power over many.

As a result, in order for the military institution of chain of command to function properly, the officer must command respect from his subordinates.

Otherwise, the military is not operating as a single force because one of the links in the chain is weakened.

An officer who lacks the complete respect of lower-ranked servicemembers in his unit faces the possibility that his orders will be questioned or disobeyed.

Once any disobedience begins, the entire unit’s structure, and consequently the entire military operation, is in jeopardy.

Second, an officer also acts as a representative of the military to the public, and those perceived to be untrustworthy undermine the legitimacy of the armed services to the public.

Officers are centrally and very publicly involved in the primary functions of the military, including transforming civilians into soldiers and directing the military’s operations here and abroad.

Owing to an officer’s important role as a leader in the military, the civilian perception of an individual officer’s conduct in theory becomes the perception of the entire military itself.

Based on these rationales for article 133, it would seem that in order to justify an article 133 prosecution of adultery, the court should find that the conduct either undermined the officer’s ability to command her unit or undermined the public confidence in the officer.

The standard under this article, however, is not so clear. In fact, the actual standard for determining which conduct is unbecoming is exceedingly and purposefully vague.

The phrase “conduct unbecoming an officer and a gentlemen” is language that originated in British military law and was later borrowed by the Continental Army during the Revolutionary War to advertise the “gentility of officers.”

The first “conduct unbecoming” offense in America appeared in the Massachusetts Articles of War in 1775, and the crime remains today as a codified statute in the UCMJ.

The language itself does not reveal which conduct specifically is unbecoming and thus criminal. This vagueness allows the standard to mold itself according to the prevailing standard of what is proper and moral.

As a result, the development of “conduct unbecoming” over time reflects the cultural changes in the American military by revealing what conduct has been determined to be improper for an officer and thus subject to criminal prosecution.

The introduction of women into the armed forces posed challenges to the article, as it is defined by the notion of officers as gentlemen and not gentlewomen.

And even though officers’ sexual improprieties have long been subject to prosecution as conduct unbecoming, controlling the sexuality of officers seems to have become the recent primary goal of article 133 prosecutions.

Because of the introduction of subjective issues, like morality and character, into the analysis of whether adulterous conduct qualifies as unbecoming, a prosecution under this article is subject to the same pitfalls as article 134, namely that the results can be unpredictable and invariably tied to the personal beliefs of the courts.

For instance, in United States v. Guaglione, the court found that an officer who visited a brothel, but did not engage in sexual acts there, did not commit conduct unbecoming.

The court justified this finding by explaining that his conduct was lawful according to the prevailing morals of the Frankfurt, Germany community, where the conduct took place.

Compare this result to United States v. Jenkins, where the court found that the officer did engage in conduct unbecoming by negligently writing bad checks, holding that these acts were disgraceful to him personally and “compromised his standing as an officer.”

Based solely on the definition of “conduct unbecoming” in case law, an officer’s extramarital affair may be unbecoming for an article 133 conviction, even though it is wholly private.

Moreover, unlike article 134, the court-martial does not need to engage in any kind of analysis as to the damaging effects of the affair but needs only to determine for itself whether the adultery amounted to conduct unbecoming. This is due to the inherently subjective nature of the definition of conduct unbecoming.

As the U.S. Army Court of Military Review stated, “It is unnecessary that the conduct amount to an offense otherwise, but ‘it must offend so seriously against law, justice, morality or decorum, as to expose to disgrace, socially, or as a man . . . .’”

By not listing any specific standards in the statute, the method and the decision as to whether the conduct offends morality or decorum are left up to the individual courts.

Viewing the lack of consistency in the analysis of conduct unbecoming and the lack of any definitive standards to demarcate this elusive concept, it is not surprising that a court-martial could convict Lieutenant Commander Penland of conduct unbecoming without any finding of notoriety of the affair or any effect it had on her competency at work.

To begin, Penland was not married and was a high-ranking officer in the Navy. Her coactor, Wiggan, was also an officer but belonged to a separate chain of command, so the relationship presented no apparent fraternization issues.

The prosecution offered no evidence of misuse of government time or resources to commit the affair, nor any evidence that the affair had a detrimental effect on either’s unit or individual performance.

In fact, the only evidence of the affair was pictures of sexual activity between two unidentifiable persons, whom Wiggan claimed to be himself and his ex-wife, not Penland.

Based on the limited information available about the prosecution’s case, it is unclear exactly how the government proved that the affair was prejudicial or amounted to conduct unbecoming.

Regardless of how the prosecution accomplished this conviction, this case demonstrates that the factors meant to determine whether an adulterous act merits punishment have little to no effect on limiting adultery prosecutions in practice, especially in the context of an article 133 prosecution.

V. THE JUSTIFICATIONS FOR CONTINUING TO PUNISH

ADULTERY IN THE MILITARY

In the past twenty years, while adultery prosecutions have almost completely fallen out of favor in the civilian justice system in America, the American military has clung to the crime of adultery by continuously and actively pursuing criminal prosecutions of adultery.

These facts give one pause to consider why the military has deviated from the civilian code in this respect. Several possible explanations arise.

They include the value of maintaining a high level of morality and honor in the armed services, the importance of upholding good order and discipline among servicemembers, and the necessity of preserving the support of the American people.

Despite the persuasiveness of these principles, prosecuting adultery in today’s military is no longer necessary to further these values and, in many cases, actually hinders their advancement.

A. Preserving Honor in the Armed Services

First, one of the oldest and most basic concepts of military life is that “there is a higher code termed honor, which holds [the military’s] society to stricter accountability; and it is not desirable that the standard of the [military] shall come down to the requirements of a criminal code.”

Members of the military have long been expected to uphold a higher standard of morality and honor than civilians. The reasoning behind this idea is that servicemembers are in positions of great responsibility: commanders must order soldiers and marines into harm’s way to carry out missions, and officers hold the keys to missiles that could start a war.

Moreover, members of the military must constantly choose to put service to their employer ahead of their personal lives and even their own safety. As a result, due to the demanding nature of being a servicemember, the military justice system accepts that it must carry a separate moral dimension not present in the civilian code.

Given the military’s high regard for morality and honor, it is plain to see why the military criminalizes immoral behavior. Nevertheless, the courts-martial have not been able to agree on whether adultery is an inherently immoral activity.

This illustrates one of the main difficulties in creating a code based on morality and honor: it is inherently subject to the whims and private moralities of the individual judges and juries involved in each case.

Perhaps a better route would be for the military to steer away from laws based solely on morality and focus on criminalizing conduct with a quantifiable detrimental effect on the performance of military duties, such as fraternization.

Adultery also brings into the discussion the preservation of the family and marriage, another central aspect to the military’s definition of honor. Adultery often leads to marital strife and sometimes the dissolution of the marriage, and the courts-martial have expressed that the military has a “particular interest in promoting the preservation of marriages within its ranks.”

The view is that because the military requires spouses to be separated for extended periods of time, prosecuting adultery will help ensure that the morale of the military will not be affected by concerns over the fidelity of a faraway spouse. The criminalization of adultery, however, does little to help this cause.

First, only the military spouse can be prosecuted, while the civilian spouse is free to be unfaithful without any legal recourse.

Second, the MCM allows punishment for adultery even when it does not actually impact the marital relationship, such as when the accused is technically married but legally separated from his spouse.

Regardless of the reasons behind desiring servicemembers to have a high moral character, it is unfair to subject military personnel to criminal sanctions for failing to live up to “a higher, unreachable standard.”

The MCM itself even states that “not everyone is or can be expected to meet unrealistically high moral standards.” Given that adultery is not uncommon in the general population, it seems unrealistic to require servicemembers to always remain faithful and unfair to subject them to criminal penalties for being only as moral as their civilian counterparts.

B. Upholding Good Order and Discipline

Maintaining good order and discipline provides another justification for the military to proscribe adultery. Discipline is crucial to maintaining the morale of servicemembers, preserving unit cohesion, and, ultimately, sustaining an effective military.

Members of the military need to be able to count on others in their unit. If one cannot trust his peer to control himself in his personal life, then some believe it follows that he also cannot be trusted in combat.

One can easily think of scenarios in which someone’s promiscuous sexual conduct could cause disorder within a unit, such as when a superior and a subordinate within the same unit have a sexual relationship, or if a soldier is carrying on an affair with the wife of another in his unit. Both of these situations would create distrust and conflict.

In the former scenario, many within the unit would become suspicious of favoritism by the superior toward his lover, and the subordinate could also feel enormous pressure to maintain the relationship for fear of retaliation.

In the latter scenario, once the unit found out about the affair, besides the natural feelings of anger and jealousy of the jilted spouse, others would most likely lose their ability to trust the cheating soldier.

On the other hand, the same type of disruption in unit cohesion could result if a soldier had an affair with the girlfriend of his peer or merely if two members of the same unit had an intense personal rivalry.

There is no law under the UCMJ, however, requiring personnel to be kind to each other, even though this would promote the important interest of unit cohesion.

Furthermore, adultery prosecutions have not been limited to cases in which the primary concern is maintaining discipline and order within a unit. Adultery can and has been prosecuted in cases involving a servicemember and a civilian with no attachment to the military.

It is unclear why the military would feel the need to regulate these relationships under this rationale. In fact, continuing to prosecute adultery could have an adverse rather than uplifting effect on morale.

The truth is that servicemembers are subject to harsh penalties when they are unfaithful to their spouses but have no resort to justice when their civilian spouses have extramarital relationships. This unfair result is a “demoralizing double standard” that would be eliminated by the deletion of adultery as a criminal offense.

C. Maintaining the Trust of the American People

The final rationalization for criminalizing adultery is that the military needs to maintain the trust and support of the American people. The proposition is that if the military loses the respect and trust of the general public, it will correspondingly lose support for its missions.

The military has already experienced the negative effects of losing public support. The Vietnam War provides an unsettling illustration of how a lack of public support can seriously harm the military.

Moreover, it is ultimately the American people who provide the personnel and funds necessary to maintain the military infrastructure. Therefore, if the military loses the public’s support, it also risks losing these critical resources.

With adultery, the presumption promoted by the military is that whenever Americans discover that a servicemember is engaged in adultery, this knowledge erodes their trust not only in that individual but in the entire organization.

Some argue that because the public entrusts the military with great responsibilities, Americans closely scrutinize the conduct of its members, even their personal sexual conduct, and any discovered impropriety will lead to a loss of trust and support.

An examination of the state of adultery prosecutions in the civilian world, however, suggests that the general public is against, rather than for, sanctioning adultery criminally.

To start with, in at least two instances military courts have found that committing adultery did not offend local civilian law and, as a result, that adultery was not inherently discrediting to the service.

In addition, the almost total absence of criminal adultery prosecutions in the civilian sector, even in the wake of numerous high-profile adultery scandals by government officials, demonstrates the reluctance of the American public to legally penalize adultery.

And finally, the public reaction to previous high-profile adultery prosecutions in the military illustrates that the public may even have contempt for these prosecutions and consequently contempt for the institution that advances them.

For instance, the outcry in reaction to the discharge of Lieutenant Kelly Flinn for adultery, echoed today in the media frenzy surrounding the discharge of Penland for her adultery charge, may indicate that the public believes criminalizing adultery charge is unnecessary and even archaic.

If the military is genuinely concerned about preserving public support, perhaps it should examine how the public actually feels about criminal sanctions for adultery and abolish the offense of adultery.

VI. WHY THE MILITARY WOULD BE BETTER OFF

WITHOUT THE CRIME OF ADULTERY

Even with the military’s numerous justifications for continuing to criminalize adulterous conduct, the military’s interests would be better advanced by removing adultery from the black-letter law of article 134.

First, usually when the military chooses to pursue an adultery charge, the adultery is merely one of a slew of more serious charges, such as rape or assault. In those cases, the adultery is unnecessary to convict the servicemember of the crime and may even be duplicitous.

In United States v. Jefferson, for example, the U.S. Court of Military Appeals overturned the adultery charges against the defendant, finding that they were “multiplicious” because they were based on the same incidents as the fraternization charges.

In that case, the adultery charges were not only unnecessary but even hurt the government’s case by exposing it to reversal on appeal for potential overreaching.

When adultery is prosecuted as an unrelated charge or as the leading charge—cases that are the exception—the armed services have shown a propensity to use adultery as a means of humiliation and retaliation.

An example of this is the case against Captain John Yee, whom the Army humiliated with an adultery charge tacked on after its original case fell apart.

Even the Cox Commission, a group brought together by the National Institute of Military Justice in 2001 to evaluate and recommend changes to the UCMJ, pointed out that the majority of adulterous acts in the military are not prosecuted, and when they are, they create a “powerful perception” that the prosecution of adultery “is treated in an arbitrary, even vindictive, manner.”

The military justice system itself has urged that adultery be dealt with informally by nonjudicial punishment as much as possible, showing that even the military realizes that the law is unpopular and unnecessary.

The needlessness of the crime of the adultery is further illustrated by the fact that existing sanctions provided by the UCMJ are sufficient to accomplish the same goals.

Inappropriate relationships that harm unit cohesion and disrupt good order and discipline are already criminalized under article 134’s offense of fraternization.

Fraternization punishes any improper relationship between an officer and an enlisted member that is prejudicial to good order and discipline or of a nature to discredit the armed forces, regardless of whether either actor is married.

Moreover, the UCMJ allows each military branch to determine its own regulations on fraternization, and as a result, each branch can also proscribe improper relationships between enlisted personnel of different ranks or officers of different ranks.

Additionally, dishonesty itself is already sanctioned by article 107—the article for punishing false official statements.

Therefore, two of the most troubling issues about a servicemember who commits adultery—that the servicemember is labeled as untrustworthy or that the affair tends to disrupt order within the unit—can be corrected without the use of the adultery offense.

Fraternization also addresses the serious problem that although some sexual conduct in the military appears to be consensual, it may actually be coercive sexual misconduct in the military context of rank, even if both servicemembers are unmarried.

The Cox Commission agrees that even though some instances of adultery amount to criminal conduct in the military context, “virtually all such acts. . . could be prosecuted without the use of provisions specifically targeting . . . adultery.”

In addition, these proscriptions promote military effectiveness with clear offenses that punish specific acts without delving into subjective and unclear factors, such as whether the public would disapprove of the conduct or whether it is immoral.

Moreover, although the military promotes the crime of adultery as a method to increase troop morale, these prosecutions may indeed have the opposite effect on servicemembers.

First, the unfair and arbitrary fashion with which the military pursues adultery prosecutions today cannot have any positive effect on the confidence and camaraderie among servicemembers.

To allow adultery to carry on all around without any repercussion and then to turn around and reprimand (punish) Lieutenant Commander Penland with a general court-martial for the same conduct seems like a very strange way to promote morale.

Additionally, the punishment for adultery is exceptionally harsh, especially considering the amount of the general population that engages in adultery.

First, whenever a servicemember receives a punishment, a negative annotation appears in the servicemember’s permanent military record. These records are examined for purposes of a promotion, and as a result, an adultery conviction could effectively end a military career.

In addition, because adultery can be prosecuted by a general court-martial, a conviction is essentially equivalent to a felony for purposes of state law, which also means that it can be reported to the Federal Bureau of Investigation’s Criminal Justice Information System.

This means the conviction stays with the servicemember long after that individual leaves the service, and thus, any court-martial conviction should not be taken lightly.

Depending on the particular state’s definition of a felony, a conviction could affect the servicemember’s voting rights, the right to own a weapon, and could even lead to a denial of retirement and Veteran’s Affairs (VA) benefits.

Furthermore, if a servicemember loses retirement benefits, there would be no recourse to appeal that decision. The benefits are simply gone forever.

Civilians who accompany the military on its missions abroad are now also subject to the statutes under the UCMJ, due to a law enacted by Congress in 2007.

As of yet, there have not been any reported adultery prosecutions of civilians under the UCMJ, presumably because civilians have less risk of prejudicing good order and discipline and their conduct does not usually reflect upon the armed services.

Moreover, adultery prosecutions against civilians may be unconstitutional, assuming that the special interest afforded to the military when regulating its personnel is not applicable to civilians who accompany the military abroad.

Even if the military decides never to prosecute civilians for adultery to avoid potential constitutional issues, it will create another double standard under the UCMJ by allowing some to philander while others subject to the same set of laws must face severe penalties for the same actions.

To avoid these potential conflicts, the entire armed services would be better served by eliminating the offense of adultery and only proscribing conduct that directly affects the proper function of the military.

VII. CONCLUSION

It is without question that the crime of adultery has fallen out of favor in the civilian justice system. Why, then, does the military cling to this outdated law?

The claim is that the regulation of some adulterous conduct is necessary to maintain the support of the American people, to uphold good order and discipline, and to preserve the concept of honor among servicemembers. Assuming the validity of these interests, they all can be furthered by prosecuting the conduct through other existing offenses.